- Leadership

Kind, Calm, and Safe: Leading in a Time of Covid-19

Are there some early leadership lessons we might draw from comparatively successful outcomes in the global pandemic? If so, then the work of Dr Bonnie Henry, Provincial Health Officer for British Columbia, Canada, is a good place to look

Dr Bonnie Henry may be the perfect case study of why we benefit from great leadership—offering some answers to those less asked questions, and a tidy exemplification of what leaders are for. Dr Henry is Provincial Health Officer (PHO) for British Columbia, the third most populous province in Canada—and Vancouver, its largest city, is the most densely populated city in the country. Vancouver lies close to the U.S. border, 100 miles north of Seattle, and is home to a major international hub with one of the busiest airports in North America. While it may be a faraway destination for many, British Columbia was certainly in the path of a great many Covid-19 journeys as the infectious disease started to spread across the globe in January of this year.

A Positive Outlier

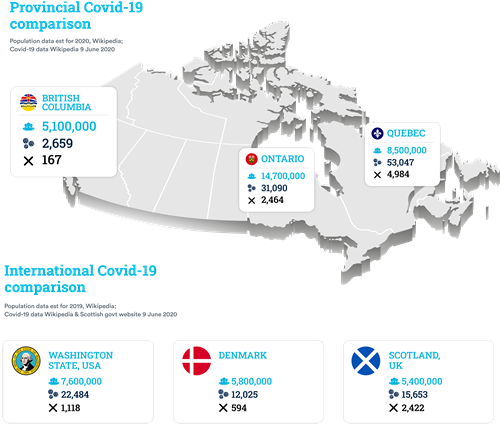

However, by mid-June the trajectory that British Columbia has travelled has been little short of astonishing. Compared to Ontario and Quebec, the most populated Canadian provinces, the infection and fatality statistics are dramatically different.

|

Province |

Population |

Covid-19 Infections |

Covid-19 Fatalities |

|

Ontario |

14.7 million |

31,090 |

2,464 |

|

Quebec |

8.5 million |

53,047 |

4,984 |

|

British Columbia |

5.1 million |

2,659 |

167 |

|

Population data est for 2020, Wikipedia; Covid-19 data Wikipedia 9 June 2020 |

|||

Whilst international comparisons can only be approximate due to differences in counting methodologies, over the border in Washington State and in similarly sized populations in Europe the figures were very different too:

|

Location |

Population |

Covid-19 Infections |

Covid-19 Fatalities |

|

Washington State, USA |

7.6 million |

22484 |

1,118 |

|

Denmark |

5.8 million |

12,025 |

594 |

|

Scotland, UK |

5.4 million |

15,653 |

2,422 |

|

Population data est for 2019, Wikipedia; Covid-19 data Wikipedia & Scottish govt website 9 June 2020 |

|||

What did British Columbia do that allowed a so much better—but as Dr Henry would state, still far from perfect—comparative outcome? In speaking to Developing Leaders, Dr Henry, in a typically self-effacing fashion, was quick to recognise that some cards had fallen their way, the most notable being that elementary and high school Spring Break had occurred up to two weeks later than in some other places in Canada. So, they had more time to prepare before the major seasonal movement of people occurred, and when the dangers were better understood.

As the Provincial Health Officer, Dr Henry is responsible for the province’s public health, and has extensive statutory powers available to her, separate from political oversight. She would certainly have been the subject of much blame had the trajectory taken a different course, and so by equal measure, the success surely carries her imprimatur.

Fortune Favours the Prepared Mind

All Public Health Officers in affluent countries are supported by extensive teams comprising deep expertise; even if they are not specialists in a particular area, they have access to the best knowledge. In Dr Henry’s case, she was the expert—having led a career specialising in epidemiology. She had been the operational lead in Toronto’s fight against SARS in 2003. There were 438 Canadian cases and 44 deaths, most of which were in Toronto. Prior to this she had worked in Uganda tackling the Ebola crisis in 2001, and early in her post-Naval career had worked on the World Health Organization’s polio eradication program. She therefore had as good an epidemiological in-the-field experience as you can hope your PHO to have.

Dr Henry acknowledges this, saying “fortune favours the prepared mind,” a quote of Louis Pasteur, the father of vaccination and disease prevention. This is a quote just as usefully and aptly applied to executive development, where instilling the importance of lifelong learning through formal programs, curiosity and broadening experience—is now paramount

For Dr Henry, her ‘prepared mind’ allowed her to see what was about to emerge, and know that British Columbia, given its position and connectedness to China, was going to be affected. “It was almost like having flashbacks, when I was hearing what was coming out of China in January. So, we started very early and I have to say that when I talked to my colleagues and said ‘I'm worried about this, we need to start preparing’—they were all 100% on board,” she recalls. Henry briefed the politicians, and as unpalatable as it was at first for them to hear, they were brought onboard too. “Once we started to have an understanding of what was going on, I sat down with the Deputy Minister of Health and went through the details. I said, ‘This is what can happen, this is what we’ll be looking at’, and he realised—okay, we need to start preparing our health system. So, together, we had things in place very early on.”

The BC approach was strongly supported by the province’s behind-the-scenes microbiologists, who were developing tests very quickly. “We have a medical microbiologist here, Dr Mel Krajden, who was also very much on top of this, and as soon as the genomic sequence came out from Wuhan we were developing laboratory testing.” In hindsight this all seems eminently reasonable, but it was very far ahead of the timeline, and well out in front of the wider global response. Dr Henry and her team were doing widespread testing before the virus arrived in the province and identified their first case on 28th January. British Columbia was testing 1000 people a day, at a time when the USA had not yet reached 500 tests in total. BC was also very early on the search for protective clothing, PPE, as they realised they did not have enough in their stockpile and that supply chains were going to be challenged, and so were managing that sourcing challenge from mid-February.

A Compassionate Response

It has been generally acknowledged that it was not just British Columbia’s early testing and early preparations for the arrival of Covid-19 that has led to the province’s remarkable record in the face of the virus. Dr Henry has also managed a highly effective communications strategy, carefully helping to shape mindsets so that people respond in a way that helps, not hinders, the prevention of the disease. At the core of this is the enabling of what she terms a ‘permissive attitude’ to testing. It was important for people to come forward and be tested if they believed they might be at risk of carrying the disease, so not just making the tests available, but also fostering a sense of community responsibility in taking the test. Giving people ‘permission’ to seek those tests out was an early and important factor in setting the public response.

Dr Henry is not wholly unfamiliar with a public role, leading health campaigns, as all PHO’s must do, and responding to population wide health concerns—but the Covid-19 crisis elevated that public role and profile enormously. She has been the public face of the crisis in BC since the beginning, leading televised daily briefings. As the world was beginning to sit-up and take notice that the virus was not something happening ‘somewhere else’, Dr Henry was already giving her briefings, starting less regularly in mid-January and increasing in frequency. She captured the population’s attention in her 8th March press briefing, prior to the Public Health Emergency being announced just over a week later on March 17, by displaying her genuine alarm for what was approaching—having to gather herself as the emotion caught hold of her. This authentic display highlighted her very real concern for the vulnerable, and the seriousness with which she viewed the situation, underlined by her explanation that she had been involved with this kind of event before and knew the stress, anxiety, and lack of sleep that was about to engulf the healthcare sector and those they had to care for. This undoubtedly had the effect of making the BC population know this was not a normal situation, and sharply focused minds.

Building on her experience, combined with an intuitive understanding that she needed to bring people with her, Henry persuaded the provincial government, at the highest levels, that they needed to be as transparent and clear as possible about what was happening, and what was likely to happen. This approach initially provoked some pushback, as it goes against standard political practice, but Henry persevered and brought the government onboard. It is to be noted that as Public Health Officer she has far-reaching powers to act without having to seek governmental permission, but she always preferred to work collaboratively, using her knowledge and experience to persuade. She told the Premier that “we need to tell people this is bad news. We need to put all the data out there, and show them what we're planning, because if they know it, and they see it, and they look at what we're watching—they know that we're being transparent, and we're not hiding things.” It was with this sense of honesty and treating the population like adults that she gained a position of trust and respect, from which a lot of the subsequent beneficial behaviour has flowed. It also explains why, unlike in many jurisdictions, Dr Henry has been the public face of the crisis, with the politicians less front-and-centre. “We [the Premier, Health Minister, and Dr Henry] have developed that relationship over the last few months, absolutely. We've kept the Premier very much involved in these decisions that we've made around travel restrictions and other things. I could have done them myself under our legislation, but we need to have the political machinery supporting it as well, or else we're at odds with each other, and that does not build confidence. What we needed to do is make sure that we keep people healthy, and that the government can take steps to fix the economic part.”

What we see in Dr Henry is a remarkable blend of expertise, allowing pre-emptive action with good management to happen in a timely manner, all wrapped in an unusually sensitive understanding of how to handle people—or put another way, leadership quality. This combination of talents highlights the three core ingredients required for successful outcomes in a whole range of fields, and crisis leadership being one—knowledge/expertise, management competence, and leadership skill. Additionally, it nicely distinguishes the difference between those two old partners, management and leadership. One is putting the mechanics in place to allow people to do their jobs, and the other is fostering the mindsets of those people to work to their best to achieve the best possible outcome— whether that be the mindsets of employees, those in healthcare; customers, the population at large; colleagues, or the rest of the government administration.

Developing Authentic Leaders

There is no single input that can lay claim to enabling these skills in Dr Henry. It derives from and is a composite of, a multitude of experiences, from family to education. Undoubtedly, her three decades of experience in the field and the networks and conversations she is able to call on, will have done most for shaping this outcome, but she does attribute some of her actions to her experience at the Physician Leadership Program (PLP) at the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business. Dr Henry attended one of the initial iterations of the program, co-led by Prof Daniel Skarlicki. The program is a custom one established by a collaboration of the British Columbia Health Authorities for their senior physicians. It was set up with the recognition that senior medics are often leading large businesses these days, with thousands of employees and huge budgets, but as highly trained as they are as medics, they often have little to no formal experience of leadership and management.

Dr Henry, reflecting on her experience on the course, attributes her confidence in sharing her own values at her press conferences with the thinking gained on the UBC Sauder PLP. “What I learned a lot of there was around how to have those hard conversations with people; and I use that technique to think about what my message is. What are the things that I need people to hear?” This has perhaps played its part most notably in the strapline that she has become closely associated with: “Be kind, be calm, be safe”. This evolved out of a children’s Q&A where she was asked by a young person what they should do if they are mocked for wearing a mask, “and I said, ‘you need to be kind with each other, because you don't know why [they are wearing them] and in some cultures, it's a sign of respect’, it's sort of the anti-bullying message. And it resonated with lots of people, because it is the truth.” Henry recognised that the crisis was going to be a long-term challenge and that as well as the direct effects of the illness and economic impacts, it would take its toll through stress, over-work, anxiety and depression, and that these were also a real threat to society, and a focus on tolerance and kindness was essential.

Prof Skarlicki, the Edgar F. Kaiser Professor of Organizational Behaviour at the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business, sees that the Physician Leadership Program plays a significant role in building capacity for leading change in the BC healthcare sector, as well as providing an important function in bringing a diverse range of physicians together from across the province. Dr Henry agrees, that by having this extensive informal network, it paid especial dividends in gaining information and disseminating it quickly during the crisis.

The program starts with a traditional but essential ‘Leading Yourself’ module, before diving into ‘Leading in Complexity’, with perspectives on the criticality of ‘horizontal influence’ across networks, and how to manage these non-hierarchical structures. It is this concept of leadership being ‘transmitted’ that Skarlicki places at the centre of the program. “It's not enough for a leader to have a great vision for themselves, they have to be able to articulate that in a compelling, inspiring way. Leaders don't get a lot of time in front of a room, in front of another person. It's down to sound bites. We've got to be really efficient; how do you craft a message that's inspiring and causes people to act differently? The program is about how to craft that script,” says Skarlicki.

To manage in complexity, says Skarlicki, requires humility and vulnerability and an awareness of the humanity required to lead—and it is very different from the old command and control approach still being used by some leaders. “It's really about seeing the humanity in the leader. As they say, never let a crisis go to waste, and this crisis is really moving us in the right direction on leadership.”

Recalling Bonnie Henry as a participant on the program, Skarlicki remembers her performing very well in some of the situations created to test their responses, again through her comfort in relying on ‘doing the right thing’. “We do a case where they learn important operation management principles. Then we stop the case and say, ‘Oh, and by the way, a patient actually died in this case and it was on your watch’, and we ask them to assume they're the CEO and have ten minutes to meet the press. During the mock press conference, instructors aggressively question the person in the CEO role. I always remember Bonnie because when she stepped up, she responded with compassion saying ‘Look, now is not the time. The time now is to take care of the families.’”

“You can never fully tell how people will perform as leaders,” Skarlicki concludes, “because you are only ever really tested in a crisis.” Dr Henry has shown in so many ways during this crisis—a more testing situation than which is scarcely imaginable—that she is both a truly authentic leader, and an authentically talented one.

ARTICLES YOU MIGHT LIKE

RESEARCH

Why organizational resilience requires adaptive leadership particularly in times of crisis

DEVELOPING LEADERS QUARTERLY MAGAZINE AND WEEKLY BRIEFING EMAILS