- Learning

The Rise of Andragogy

The growing understanding of the theory and practice of teaching adult learners

We are living in a time of great challenge in education. More people are going to university than ever before, yet debt-ridden university students increasingly question the value for money of the education they receive. Young people who have completed their university education experience considerable levels of graduate unemployment (or underemployment), yet employers bemoan the lack of skilled employees being produced by our universities. It seems that something about our traditional educational model does not fit comfortably with current societal and employment needs.

Much of our educational model, and indeed many of today’s leading educational institutions, date back to Victorian times. Most people at that time expected to stay in the same job – and even in the same firm – for the whole of their working lives, a pattern that held true well into the 20th century. The educational model was therefore front-end loaded; by and large, learners received all of their education during the first two decades of life, and then went out to work. Teachers and professors ‘owned’ all the knowledge, and students ‘sat at their feet’ to learn it, in a formal master-pupil relationship.

Times, though, have changed. People no longer stay in the same job all their lives; today, young people are changing jobs twice as frequently as their parents did. Access to knowledge has shifted radically, too – thanks to the Internet, knowledge is often freely available; some enterprising students are even designing their own courses of study from online materials, putting together ‘free MBAs’ that draw on some of the best speakers and teachers in the world. Another, less obvious, change is a shift in the people we listen to. In everything from customer reviews on Amazon to ‘how to’ videos on YouTube, we are now as likely to seek out information from our peers as from our educators.

The great American futurist, Alvin Toffler, commented that the key 21st century skill would be the ability to “learn, unlearn and relearn.” Einstein himself famously remarked that “Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school.” Both these observations make important points about the changing nature of education; it is no longer about learning facts (knowledge) but much more about learning how to learn, about adapting ourselves to a world where people change careers several times, and the business context is altering faster than most of us can adapt ourselves.

Many educators are now adopting a different approach to education, amending traditional pedagogy and adopting approaches that are informed by experiential learning and by andragogy. Pedagogy, the method and practice of teaching children, is traditionally based on transmitting knowledge. There are good reasons for this - everyone needs a base level of knowledge on which they can build. Take learning a language, for example; you need to learn nouns and verbs, the basic building blocks, before you can make a sentence– but that is insufficient to hold a nuanced or rhetorically impactful conversation. You need to practice, to make mistakes, to apply the language in different situations, before you become fluent or even comfortable. Experiential learning, working in teams on projects and applications, is having a major impact on our approach to education.

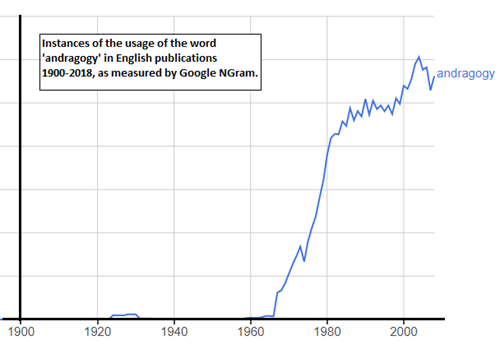

For educated adults this base set of knowledge is already acquired; the next step is to make more sophisticated connections and deepen their understanding. This requires a different learning approach known as androgogy, the theory and practice of teaching adults. The word has been around for over a century but was popularised by the American educationalist Malcolm Knowles in the 1980s and 90s and has been gaining increasing usage this century.

I believe we are now at the start of a distinct shift where the focus on education is, rightly, on learning rather than teaching. The andragogic approach makes more use of self-directed learning, experiential learning, and coaching (which may come from the professor or may come from peers). Andragogy makes positive use of the prior experience of the learners, so that classroom sessions become moderated debates rather than formal lectures. It can be cathartic and challenging, as learners test textbook theories and models against their own experiences of the workplace. It can be more playful, more experimental, more emotional than a hub-and-spoke classroom session could ever be. It can adapt more easily to different learning styles, incorporating multiple styles in any well-designed program. This brings complexity to designing and delivering learning programs at an institution like ours at Cranfield, but it also brings richness.

Degree courses and executive programs at Cranfield are carefully designed, with a great deal of thought given to the learning approach, particularly on how we use valuable face-to-face time in the classroom for facilitated discussion rather than simple content delivery. We also design team working tasks and bring together team members with different experiences, for greater learning richness. To help us do this, we are making more use of team working areas with flexible seating spaces and creative walls and so on. We also design in experiential visits and simulations. The design of programs is becoming increasingly sophisticated; while the broad objectives may seem familiar, the careful planning of the order and amount of time devoted to different segments of programs is much more scientifically based than before. This expertise – how to design for post-experience learners, and to leverage the work and life experiences they bring - is the real value that we bring.

ARTICLES YOU MIGHT LIKE

VIEWPOINT

For Thomas Misslin, transformation rather than training is the aim of executive education at emlyon business school

DEVELOPING LEADERS QUARTERLY MAGAZINE AND WEEKLY BRIEFING EMAILS